Photography depends on distance, yet social distancing does not lend itself to photography.

In the last two and a half months of quarantine, I’ve been taking pictures, of course. It’s how I go through my day, how I make sense of things. It’s what I share with family on WhatsApp and iPhoto, with friends on Instagram and Facebook. But my photos have not really helped me make sense of this moment, and neither, really, have the photos taken and published by others across the globe. It may be too early to think about how the pandemic will be remembered or memorialized but I would venture to say that, besides the striking blow-up of the image of the coronavirus itself as seen through an electron microscope, no potentially iconic photograph of this pandemic has yet emerged.

Indeed, between the remoteness mandated for public health and the ability, microscopically, to expose the “invisible enemy” inside our bodies, image-makers have struggled to find the middle-distance that might enable them to bear witness to both the global and the intimate scale of this event.

Cancellation, isolation, distancing, quarantine, stay at home orders. These are obstacles standing in the way of photographic images that might succeed in framing the pandemic and its social and political effects in ways that help a broad public process unprecedented suffering, both enlightening and mobilizing us. Events, rituals, group gatherings that provide the occasion for photography have been canceled. Weddings, bar mitzvahs, even funerals are limited to an intimate family unit, attended by others on Zoom. Birthday and graduation celebrations are Zoom get-togethers supplemented by celebratory motorcades of neighbors in small towns.

Sarah Lewis’s editorial in The New York Times, published in early May 2020 and poignantly entitled “Where Are the Photos of People Dying of Covid?” beautifully articulates what we expect of photography in moments of crisis, and what in her opinion we are not getting. We are not seeing, or not being allowed to see, the human suffering, Lewis argues; we do not see the dying. People are reduced to statistical numbers. Evoking iconic images from earlier crises that resulted in mass protest and political change—AIDS, the water catastrophe in Flint, Michigan, Matthew Brady’s photographs of Civil War casualties, and the Farm Security Administration’s images of poverty during the Great Depression, among others—the article assumes that photographs can offer visceral knowledge inciting action and response. “Without these pictures,” Lewis concludes, “the virus is harder to combat.” Only through seeing can an event such as this one “penetrate our hearts, as well as our minds.” But are these assumptions about the mobilizing power of vision and the mediating role of photography still valid in the absence of that middle-distance?

There are, of course, many photo projects and myriad photos circulating. We are in late May and in the Northeastern United States spring is advancing. There is solace in photographing blooming fruit trees, lilacs and magnolias, long awaited cherry blossoms, or, as in my own case in late spring New England, fields of yellow dandelions. In cities and towns, it’s hard to resist photographing the closures—boarded up stores, theaters, museums, and schools, some with moving quickly-produced signs reading “WE MISS YOU.” Everywhere, we find drone images of empty streets and squares, wide-angle views of malls and airports, close-ups of masked impenetrable faces. “Can you see that I’m smiling?” has become a meme. All these images continue to produce disbelief. And, then, the equally shocking re-openings, showing people with no masks, too close together, on beaches or in parks, provoking anxiety and fear.

But Lewis is looking for something else, for more of the actual suffering. In response, Reading the Pictures recently re-published a number of images from the last two months showing that “Here are the Pictures of People Dying of Covid.” How can we explain this divergence? Perhaps they are both right: perhaps there are a lot of images, images by makers who attempt to negotiate distance and proximity, and perhaps they still somehow fail to do what we need them to, or what we wish they would.

What are the various Covid-related image projects asking of their viewers? How do they touch, move, and mobilize us; how do they help us understand and bear witness?

Despite the risks of breaking out of a mandated bubble of protection, some photographers have succeeded in producing searing documentary projects from as close a vantage point as is possible right now. We do see images of the sick and dying cared for by nurses and doctors, covered in protective gear. Photographers working as emergency responders, like Andrew Renneisen, or medical professionals, like Karen Cunningham, are themselves taking pictures to bear witness. Working for the New York Times, Philip Montgomery, who has photographed inside a Bronx funeral home and in two New York hospitals for over two months, also documents the painful effect this work from the inside has had on him.

John Moore also gets close to give us intimate peeks into one family’s extraordinary story of giving birth with Covid-19, and a teacher’s care of the newborn until her parents’ recovery. His Instagram followers get daily updates of this drama and I can almost feel the collective sigh among us when baby Neysel is reunited, held, and hugged by her mother Zully. During social distancing, at a moment when the screens of our phones, tablets, and computers provide our only spaces of social interaction, I am grateful to be included in this virtual embrace.

Images of the mass graves at Hart Island in New York and other mass graves, however, are taken by remote drones. And, from a safe distance, we see long lines at unemployment and food distribution centers, as well as images of protests by nurses and workers demanding hazard pay and protective equipment. They hold signs, asking us for solidarity, from a distance.

Forbidden to travel to sites of public interest, or even to leave their spaces of quarantine, many photographers have had to find creative ways to bridge the divide between those who have the possibility to isolate and those essential workers who enable the isolation. Haruka Sakaguchi initiates her Quarantine Diary from her bed and out of guilt for her privilege. Deb Willis, known for her rich images of black life and black beauty, has been populating her Instagram feed with beautiful photos of New York high rises taken from her window. Similarly, Argentinian photographer Julio Pantoja observes a strict quarantine by taking pictures out of the window. While quarantined, conflict photographer Paolo Pellegrin found a new subject when he photographed his family for the first time. The 400 members of the international collaborative Women Photograph have created a communal diary on Instagram sharing personal experiences during the pandemic.

In the search for a middle-distance, the line between image-makers, curators, and directors has become blurred, and the mediating technology has entered the frame. We see screens within screens. In collaboration with The Nation, The Magnum Foundation is sponsoring a weekly series on “The Invisible Frontline,” covering topics such as food workers, health care workers, parenting during a pandemic, and the fate of sex workers in Puerto Rico. The aim, precisely, is to make the invisible visible. The resulting photo essays are moving and personal, offering curated collections of self-portraits of parents and children and of sex-workers taking photos or videos on their laptop or phone cameras to disseminate to paying customers. “The Invisible Frontline” enables us to get glimpses of how some vulnerable populations cope, using selfies, Facetime, and Zoom to engage their collaboration in the process. Similarly, British artist Heather Glazzard appears in a small square in the Facetime portraits they make, in collaboration with each subject, of their queer community in Britain. In contrast, U.S. photographer Annie Tritt, on assignment for the New York Times, meticulously stages and directs her subjects’ portraits via Zoom but remains outside the frame.

These are not single iconic images, but evolving photo essays, including voices and stories. They are products of an interaction—almost a form of touch—between image-maker, subject, and viewer. In a world in which we can only hug or touch members of our own household, while sophisticated technologies are being developed to produce a touchless form of sociality, the insights offered by photography cannot be limited to a distant visuality. To move a broad public, they need to invoke various senses and satisfy multiple needs.

Visuality is haptic, embodied, material; photographs resound with timber, frequency, and sound. They provoke smell and touch. They can move us affectively, viscerally. But what qualities do they need to provoke us to act collectively?

Images of empty New York streets, restaurants, and museums are astounding; as a slideshow accompanying Frank Sinatra singing “New York, New York” in Spike Lee’s short film, they moved me to shed tears of loss and longing. Similar images from cities around the globe gain emotional power in a YouTube video in which Andrea Bocelli sings “Amazing Grace” on the empty square in front of the Milan Cathedral. In each of these cases, images are multiple, they move, they participate in collaboratively generated multisensory narratives of vision, sound, and touch.

Single still photographs themselves can and do produce such visceral responses, of course. As visual studies scholars have argued, visuality is haptic, embodied, material; photographs resound with timber, frequency, and sound. They provoke smell and touch. They can move us affectively, viscerally. But what qualities do they need to provoke us to act collectively? That is a question that has faced photographs of disaster from the very beginnings of the medium. In the absence of a necessary middle-distance that can draw a broad range of viewers into the image as participants and co-witnesses to the events, this question has become more pointed and more urgent.

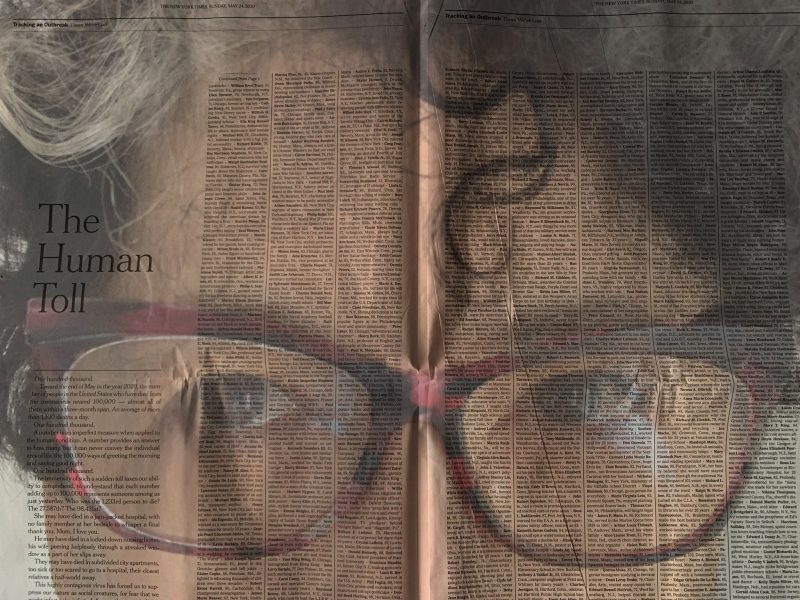

For over 20 years, Lorie Novak has been collecting, studying, and categorizing the images displayed on the New York Times front page in a project she calls “Above the Fold.” Often, she says, photos, especially traumatic photos, “get under my skin.” She transmits that powerful response by embedding these photos in single images, diptychs or triptychs that feature her own eyes and face, wearing glasses or not. In some videos her eyes blink. Part of a larger project she calls “Photographic Interference,” these works invite us to look at media images with and through her, thus clarifying how they shape the ways in which we look, how they interfere in our daily lives, what, in fact they do to us, as we bear witness not to the events themselves, but to the photographs of the events, or to the photos as events.

Not surprisingly, from mid-March until late May most of the “Above the Fold” photos have concerned the Coronavirus. Novak has continued to collect and to mediate some of these photos with her eyes and glasses. Doing so, I believe, she brings them closer, into a middle-distance, reframing our field of vision within hers, enfolding us in an intimate, shared space of looking. She does this by making her open, unmasked face, her very interior self, vulnerable to the events that are grafted onto her skin, or that “get under” it. And that skin, the skin of the image, our screen, becomes a space where we can allow ourselves to be touched.

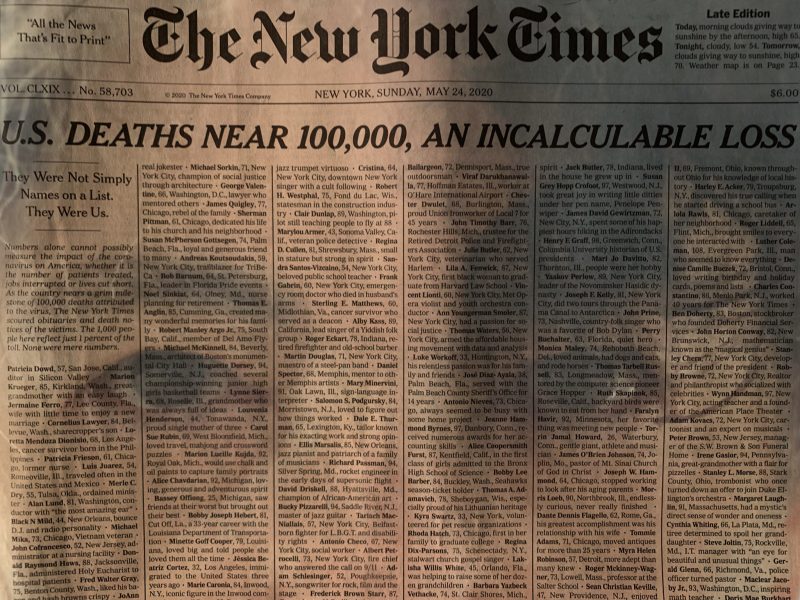

May 24, 2020, Memorial Day, was the day when deaths from Covid-19 in the United States approached 100,000 and the New York Times sought a way to bring the magnitude of loss home to its readers. Editors considered filling the front page with a grid of portraits of the dead. Instead, they thought it would be more powerful to list as many names, ages, home-towns, and single descriptive phrases for each person drawn from local obituaries as would fit on several pages of the paper. No images, no fold, no frame.

Novak created two images to frame this devastation for her viewers, one with glasses, and one without. Like her, I first wear my glasses and read the names, marvel at the ages, try to imagine the life, move to the next. Then I take my glasses off to cry. As Novak’s eyes stare out at me directly or through her glasses, however, they demand even more. They show me how the news interferes in my everyday life. They provoke me to read further, to look and to see, and to figure out how, in this moment of isolation, I might join with others to act.

Of course, we all need to see as many images as we are able to see. Yet, I believe that Novak’s is the kind of photographic project that is especially helpful at this moment. Not one that shows us more or different kinds of scenes, but one that allows us to feel what we are already seeing.

—Norwich, VT, Late May, 2020

Over the last few days, another set of images has overtaken our field of vision. Across the United States and in numerous other places across the globe, protesters are risking infection to rally against recent incidents of racial violence against Black Americans by the police. A viral video of the brutal murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis by a police officer, with other cops watching, unleashed this continuing mass action. Preceded by the killings of Breonna Taylor in Kentucky and Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia, and at a moment when communities of color have suffered massively disproportionate losses from the pandemic, this latest violent incident has proven intolerable.

Protests, and especially arrests, make it impossible to maintain social distance. Journalists are reporting on the ground and in real time and photographers are able set up powerful shots. Cell phone images posted on social media move ever larger crowds to join peaceful marches. Protests turn violent as evening descends. One image of a man carrying an upside down flag and walking in front of a burning building almost immediately emerges as iconic.

We have seen these videos and these images before. We know how to look. Each time they are searing and they succeed in mobilizing us.

But the pandemic is still raging and we don’t yet know how to mediate it visually.*

—Norwich, VT, June 1, 2020

*With my thanks to Susan Meiselas, Lorie Novak, Leo Spitzer, Diana Taylor, and Laura Wexler for their helpful suggestions.

Marianne Hirsch teaches at Columbia University in New York. Her most recent books are The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust (2012), School Photos in Liquid Time: Reframing Difference (2020), coauthored with Leo Spitzer, and the coedited volumes Women Mobilizing Memory (2019) and Imagining Everyday Life: Encounters With Vernacular Photography (2020).

Lives Lost on 2 Cruel Days. Photo: Lorie Novak. ©Lorie Novak, 2020

Schools, May 2020. Photo: Lorie Novak. ©Lorie Novak, 2020

The Human Toll, New York Times, May 24, 2020. Photo: Lorie Novak. ©Lorie Novak, 2020

100,000 Deaths, New York Times, May 24, 2020. Photo: Lorie Novak. ©Lorie Novak, 2020